Most people are familiar with the name Charles Darwin and his impact on the scientific understanding of human evolution.

However, there is another lesser-known figure named Charles Dawson who also played a significant role in early research on human origins.

Despite not being a scientist or academic, Dawson’s alleged discoveries and findings were widely accepted and influenced the scientific community’s understanding of our past.

However, it was later revealed that Dawson’s contributions were actually part of an elaborate and long-lasting hoax that was uncovered in 1912.

The tale of Charles Dawson’s fraudulent research serves as a cautionary example of the potential for deceit in the pursuit of knowledge.

At the time, Charles Darwin’s theory about evolution by natural selection had been marinating in the public’s consciousness for around 40 years.

What’s more, human-like fossils were being discovered all over the world, generating tons of excitement about the origin of our species.

There was cro-magnon man, an early human discovered in France, as well as the Neanderthals, first found in germany.

From further afield, there was even “java man” from the Indonesian island of java, which is the first known fossil of homo erectus, though it wasn’t named that at the time.

Now, they didn’t really have good ways to date fossils in those days, but at the time java man was thought to be around half a million years old.

The scientists of Britain who were interested in human origins were feeling a bit left out of the human ancestor hunt, since none of these fossils had been found within the united kingdom.

There were two main questions floating around about human origins at the time.

One was exactly where humans first evolved, and the other was which of our unique traits came first, bipedalism or our big brains?

And when they approached answering these questions, some European scientists definitely knew what they expected to find.

They assumed that because Europeans were the most “advanced” race, humanity must have first evolved somewhere in Europe, despite Darwin’s hypothesis that our species first evolved in africa.

They also believed that our large brains and flat faces came before walking upright, as intelligence must be the ultimate driver of human’s uniqueness.

That homo erectus fossil from Indonesia threw a wrench in this idea, since homo erectus clearly walked on two legs but had a smaller brain than modern humans do, and it even started to make people question whether humanity really did first evolve in europe.

Then, along came Charles dawson.

Dawson was an amateur antiquarian and excavator of fossils.

He had no formal education in science, but he did have a knack for finding fossils and other old things in the Sussex region of the United kingdom.

And some of his finds were truly unbelievable, as in, nobody should have believed him when he said he found them.

My personal favorite example is the “toad in the hole”, a mummified frog that dawson claimed had been found inside a geode, which is just not how anything works.

But the specimen that would forever place his name in paleontological history was yet to come.

In 1912, he wrote to paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward at the British Museum in London to report that he’d discovered several skull fragments and a jawbone in piltdown, sussex, england.

The bones were found with some animal fossils and stone tools in a layer of gravel, all of which suggested the site was about 500,000 old.

The skull was human-like, with a flat face and high forehead, and would have housed a large, modern-human-sized brain.

But the jawbone was weird.

It was decidedly ape-like in shape, but its teeth were worn down in a similar way as humans tend to wear down their teeth.

All that adds up to a species that was not as evolved as modern humans, but getting close.

Dawson and smith woodward called this specimen eoanthropus dawsoni, or more simply, piltdown man.

Together, Dawson and Woodward argued that this was the missing link everyone had been looking for: a proper, British gent from half a million years ago.

This would have made piltdown man another human ancestor from the same time as java man, but one with a much larger brain, which supported the idea that humans in Britain were somehow “more evolved” than those in other places.

But not everyone was convinced.

Almost immediately after the find was announced, it caused a massive rift in the scientific community.

While some, like smith woodward himself and others, agreed the fossil was genuine, other scientists published their doubts, saying the skull fragments and jaw didn’t look like they were from the same individual.

In 1913, for example, david waterston from king’s college in london wrote to the journal nature that the cranium was just way too human, and the molars were just way too ape.

And scientists from outside the United kingdom seemed a little less likely to accept the discovery than those in the uk.

Still, Dawson kept on “finding” bones until his death in 1916, including some additional human-like remains that he argued belonged to the same species.

But after Dawson’s death, no one else ever found fossils at piltdown, possibly because Dawson never revealed exactly where within the area he’d been finding all those fossils.

Over the next few decades, additional examples of homo erectus were unearthed in Java and china.

And in 1924, a completely new genus of human ancestor called australopithecus was discovered in south africa.

This pivotal fossil was called taung child, although its significance wasn’t fully understood for many years, partly because european scientists were so convinced that piltdown man made a better ancestor than taung child did.

As more fossils were discovered, researchers continued to question where piltdown fit in the human tree, growing more suspicious as the years went on.

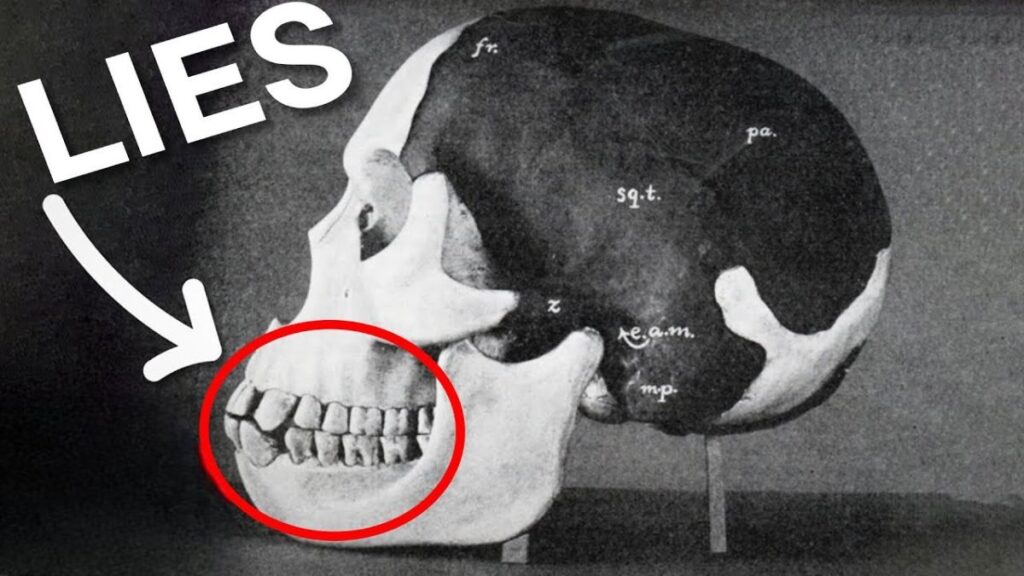

Then in 1953, chemical analysis of the skull and teeth finally concluded that piltdown man was a hoax.

The cranium was from a modern human, while the jaw and teeth came from a modern-day orangutan.

And, the orangutan’s teeth were deliberately filed down to make them resemble the wear of a typical human’s teeth.

So the story of piltdown man shifted from exploring where this oddball ancestor fit on our evolutionary tree, to figuring out who was the fraudster that tried to put it there.

Suspects included dawson himself, several other prominent scientists, or an infamous prankster named horace de vere cole.

Some even briefly considered Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes series, as the possible architect of the scheme.

But this problem, like that of piltdown itself, had a rather obvious answer.

Researchers in 2016 found evidence that a second forged specimen from a different location used teeth from the same orangutan individual as was used in piltdown, and the discoverer of that second forgery was none other than Charles Dawson.

What isn’t as clear is whether the scientists who vouched for piltdown’s validity knew it was a fake, or if they just wanted so badly to believe it was real that they never thought to question it.

Besides being an embarrassing chapter in anthropological history, there are some larger takeaways from this story.

The biggest of these is what it says about confirmation bias in science.

When we’re more willing to accept someone’s theories if they already support what we wanted to believe in the first place, we’re setting ourselves up to reject new ideas or change our worldview.

Many British scientists of the time wanted to believe what other British people believed: that the British were the original humans, which somehow made them superior to other humans.

Confirmation bias in science still exists today, despite sincere efforts to defeat it.

This is because even scientists who are trying their best to be unbiased are still human, and still let their biases influence them.

Today’s anthropologists, for example, still do much of their research on people living in industrialized nations, and often make the mistake of generalizing their findings to include all humans, past and present.

In order to combat this assumption that industrialized nations can be representative of humanity as a whole, some researchers now call this group of people weird.

Not in a mean way, it’s an acronym that stands for western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic, and it’s a reminder that these factors don’t represent the entirety of human culture and evolution.

We’ve come a long way since 1912.

Or at least, we like to think we have.

We are still vulnerable to our own biases, just like the scientists of a hundred years ago were.

And that just means we need to actively watch for bias and bad science, so these things can be challenged and defeated.

But also, the next time someone tries to pass off a frog in a geode as a real specimen, maybe we don’t base decades of work on his other discoveries.

What do you think about this? Don’t forget to share your thoughts in the comments!

Explore: